A friend recently forwarded to me an article discussing the difference between self esteem and narcissism Most people know the meaning of – or are familiar with – the term ‘self esteem’. If you don’t know what narcissism means, google it. Most definitions sound very much like Yeshus, and arrogance. Being absorbed in oneself.

Depending on how we look at things, these two terms can seem related, and even resultant of the same kind of upbringing. But as is often true, especially in Chassidus, two similar things can be, in reality, polar opposites.

As an example, the Rebbe mentions the difference between Tzedaka, and Charity. Seemingly the same thing. But the Rebbe explains that, in fact, these are two opposite concepts. Charity is the idea of providing to another who is underserving. And Tzedaka – from the root of Tzedek, Justice – is the giving of what rightfully belongs to the other and is the complete obligation of the giver to do.

And the results are also completely opposite, both in regard to the giver as well as the receiver.

With Charity, the giver can feel that he or she are very great and may result in feelings of arrogance and grandeur. And the receiver may feel embarrassed and degraded to have to beg for a handout that he doesn’t really deserve.

On the other hand, Tzedaka, the Torah tells us, is simply the transfer of the funds to the rightful owner. Just as Hashem provides to me my Parnassah through my job and my paycheck, Hashem has provided to the poor person through my paycheck as well. Ten percent of that check is not mine to begin with and must be paid to its rightful owner. When I am giving Tzedaka, I am simply paying my obligation and there is no room for feelings of greatness. And the recipient does not need to feel that he is receiving something he does not deserve. In fact, he may even feel that he has the opportunity to allow the giver to do a Mitzvah.

Likewise in our discussion of self esteem and narcissism. Both obviously have to do with the way we view ourselves. But in the case of narcissism, the result is that since I am so great, i am entitled and and expect others to serve my needs.

On the other hand, a person with very high self esteem feels secure enough to give to others and is not afraid of ‘losing out’ by giving in to the other.

The author was making the argument that these two opposite feelings result from two similar but, again, polar opposite parenting approaches. A parent raising a child to believe that she is special can lead that child to believe that she deserves more than others. Whereas a parent who tells a child that she is loved (as in “I love you”), leads to a child who feels valued in who she is.

Of cours e, this is a grossly oversimplified description, but I believe that this is in effect what Chazal tell us in regards to אהבה שאינה תלוי׳ בדבר, love that is unconditional. When we tell our children that they are special, that means something about them makes them special. This can bring to the contradictory feelings that I am better than the other because I have this unique “something” that makes me special, while also making them insecure because they believe that without that “something” they are worthless, and the result is a life of trying to defend and uphold that something.

e, this is a grossly oversimplified description, but I believe that this is in effect what Chazal tell us in regards to אהבה שאינה תלוי׳ בדבר, love that is unconditional. When we tell our children that they are special, that means something about them makes them special. This can bring to the contradictory feelings that I am better than the other because I have this unique “something” that makes me special, while also making them insecure because they believe that without that “something” they are worthless, and the result is a life of trying to defend and uphold that something.

However, when a child is raised with the “I love you” approach, then the message comes across that what I love is “YOU”, not something about you. This leads to an intrinsic feeling of self-worth based on me being me, or as the Alter Rebbe tells us, that we are worthy from the very fact that we are a חלק אלו-ה ממעל ממש. This is the true value of a person and nothing can take that away.

I think that is what the Rebbe means in the quote we mentioned on our site. That the two seemingly conflicting feelings of Bitul, and self-worth are, in reality, not only not conflicting, but serve each other. A person with a strong sense of self worth, will have no problem ‘Mevateling’ himself to the other because he sees no risk and no contradiction between his existence and the other’s.

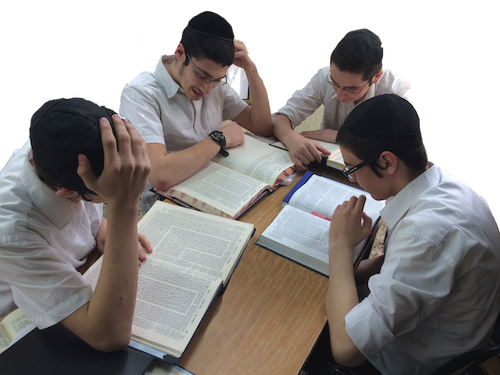

This is the attitude we try to transmit to our Talmidim. Each Talmid in Mesivta Lev Tmimim is made to feel that his worth is not dependent on his accomplishments, academic or otherwise. At the same time, we try to impress upon him that since he is of infinite value due to his very essence, then his potential to succeed is tremendous and this should motivate him to live up to that potential, and not in order to get approval, but rather to fulfill his role in this world which only he can do.